Heidi Kraay

2024: 100 thousand praises

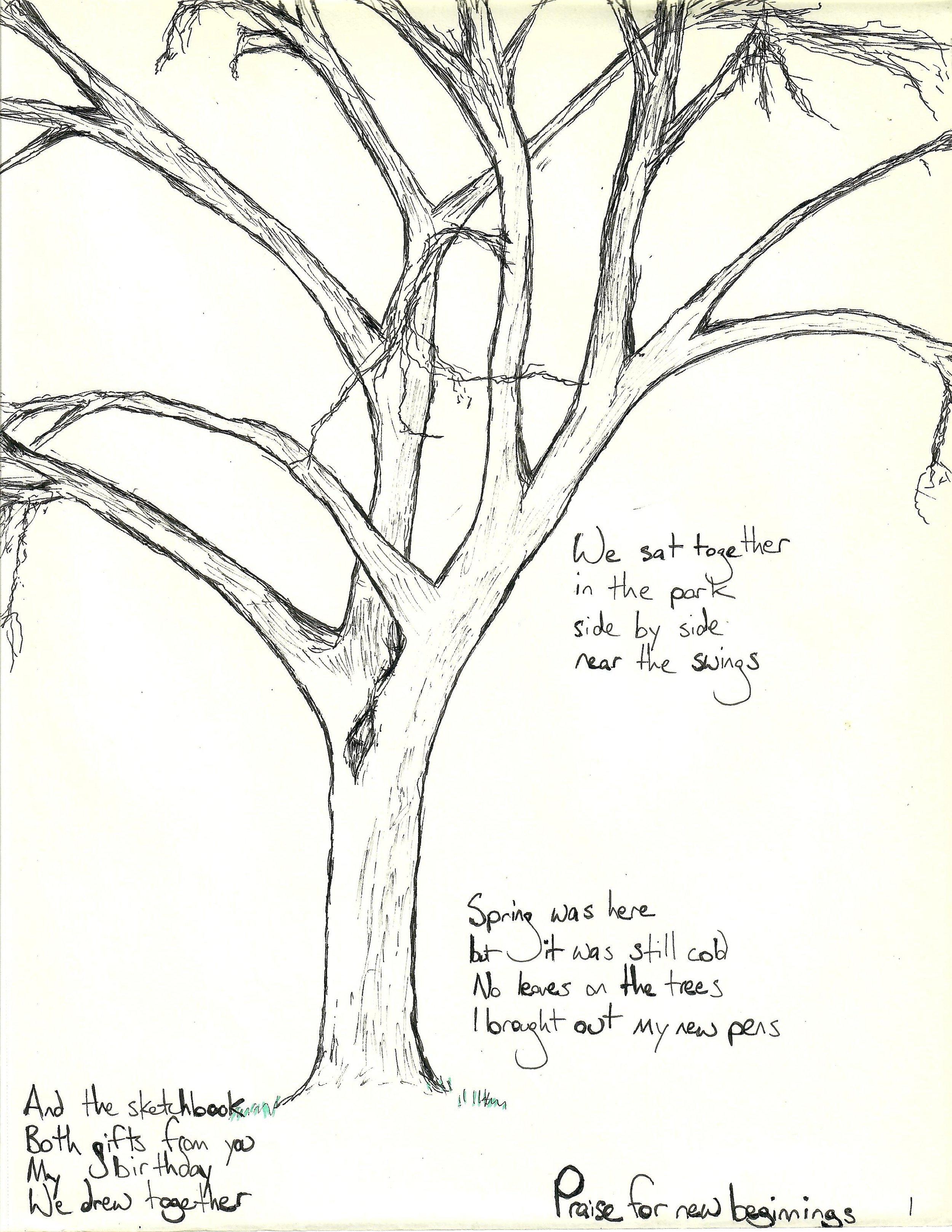

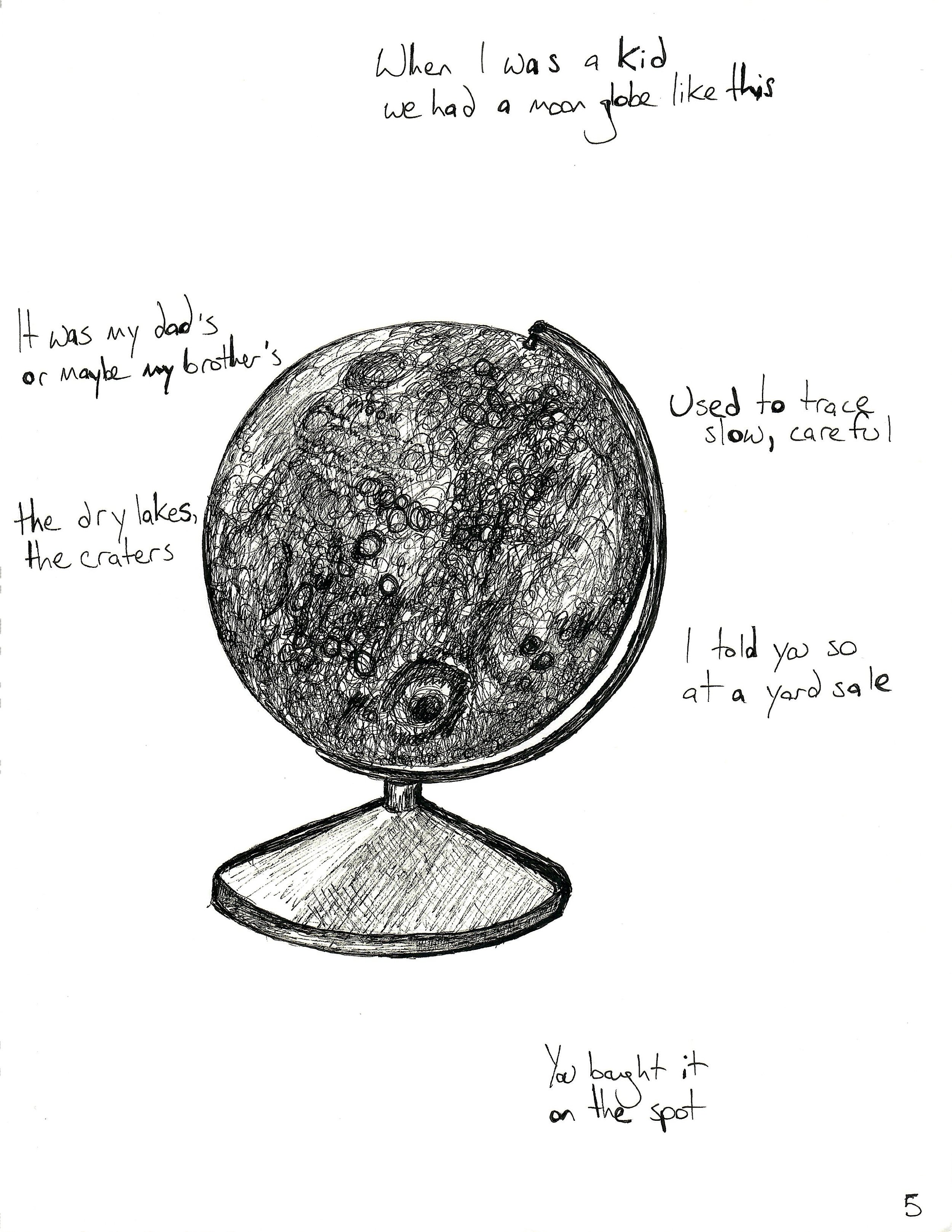

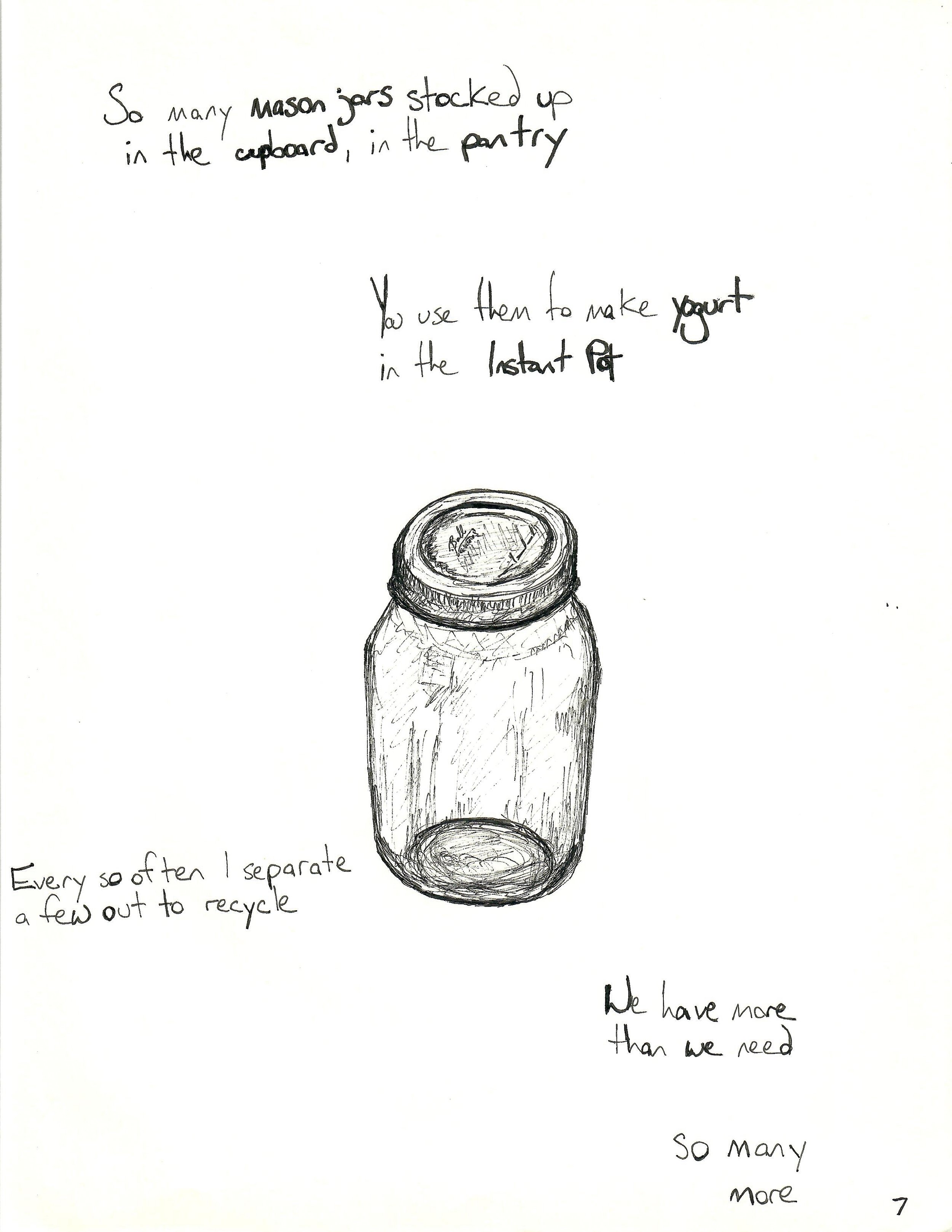

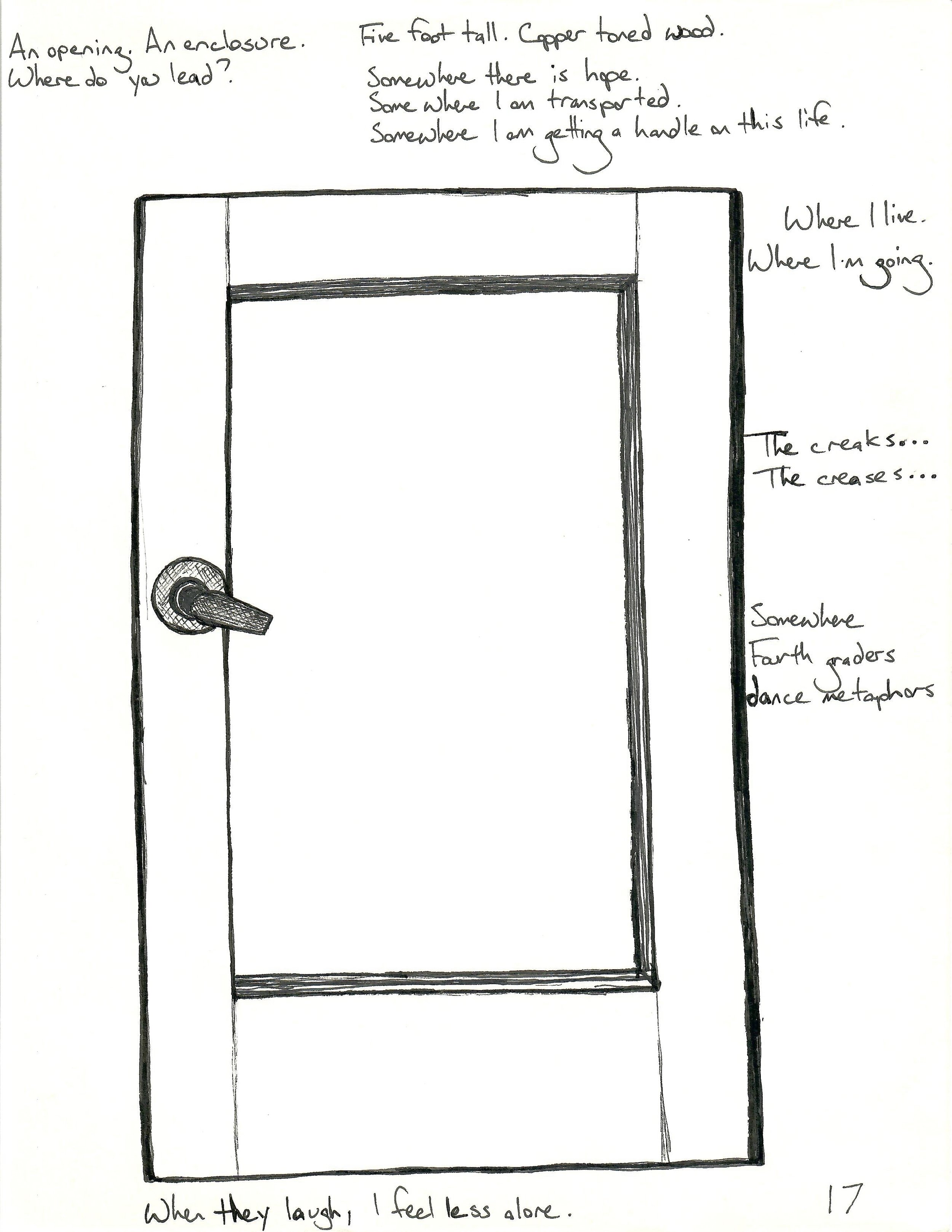

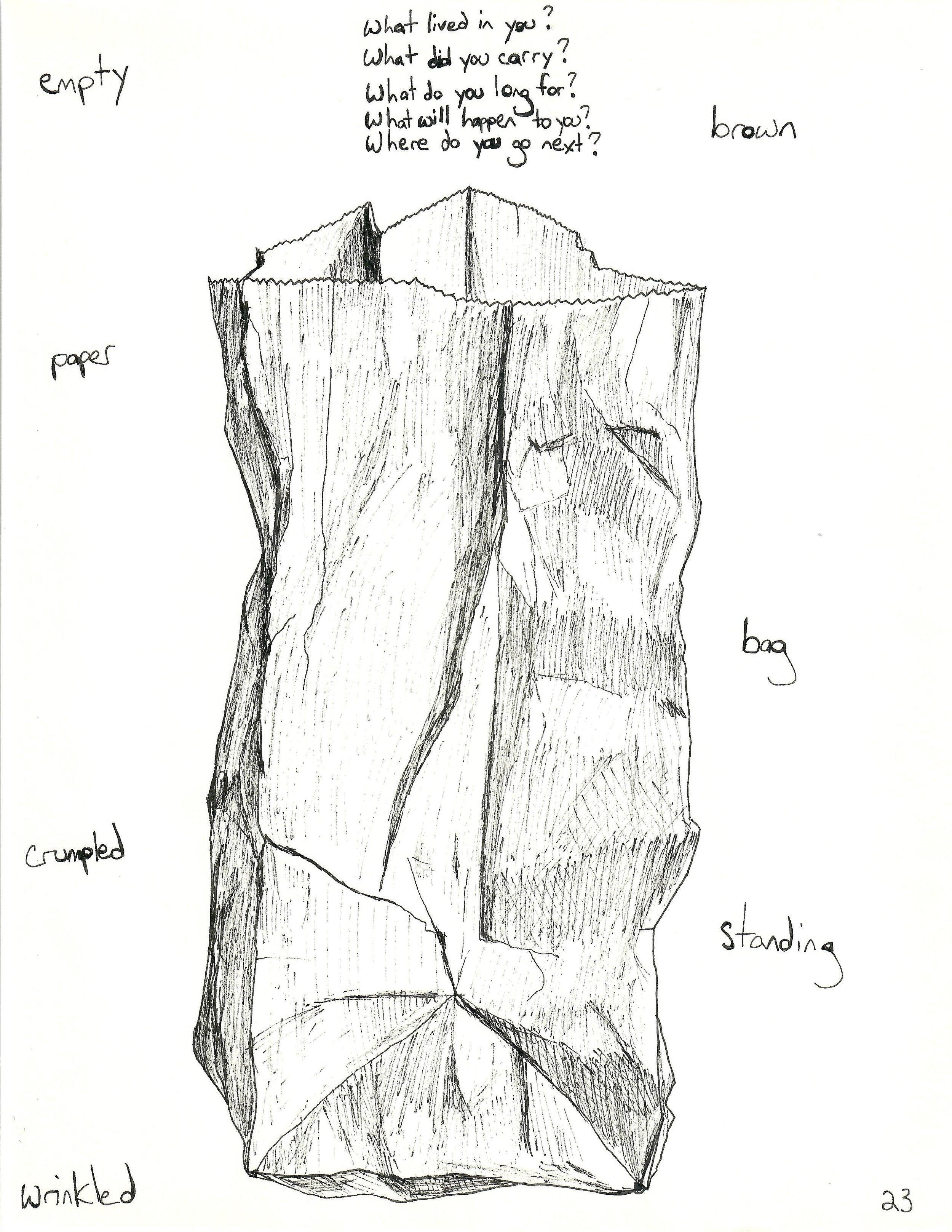

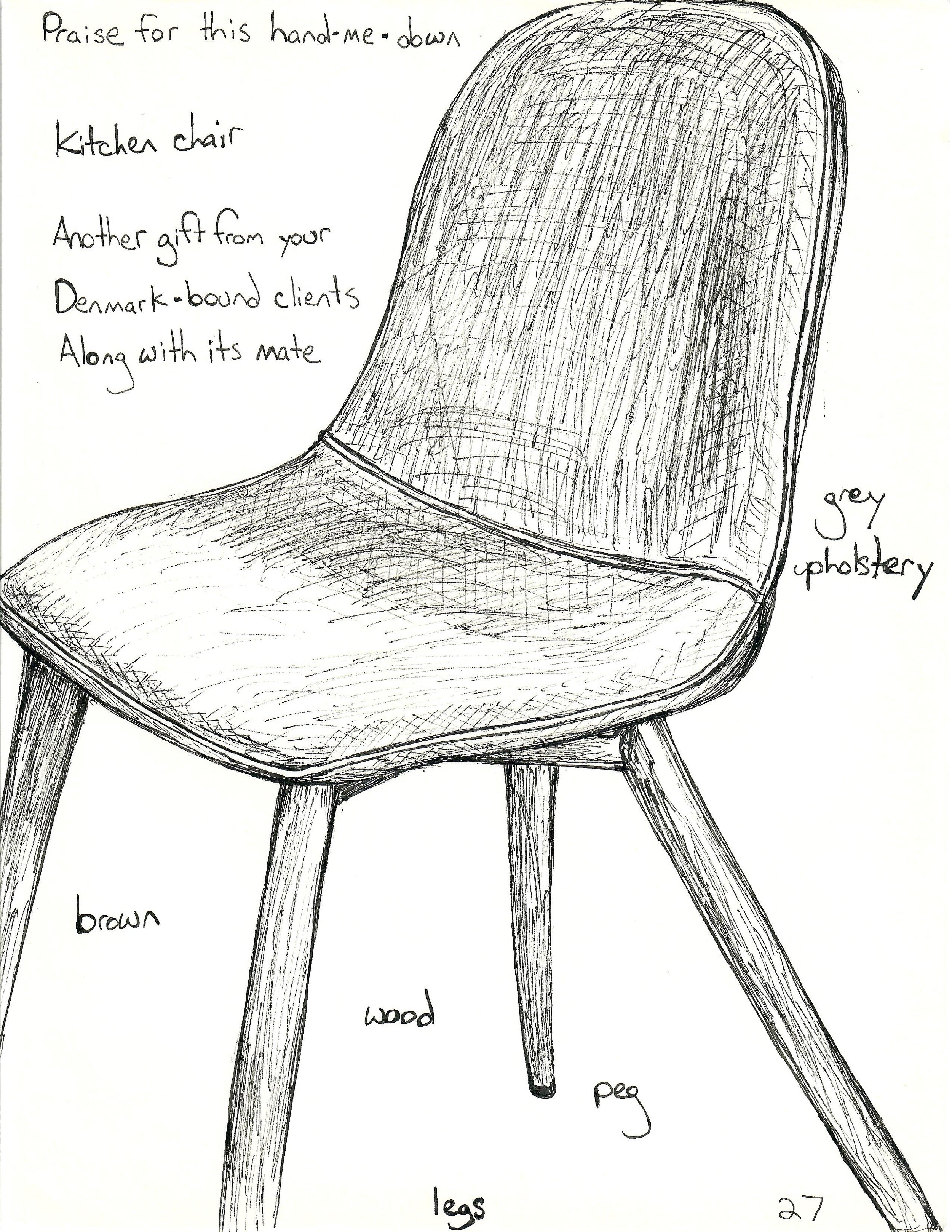

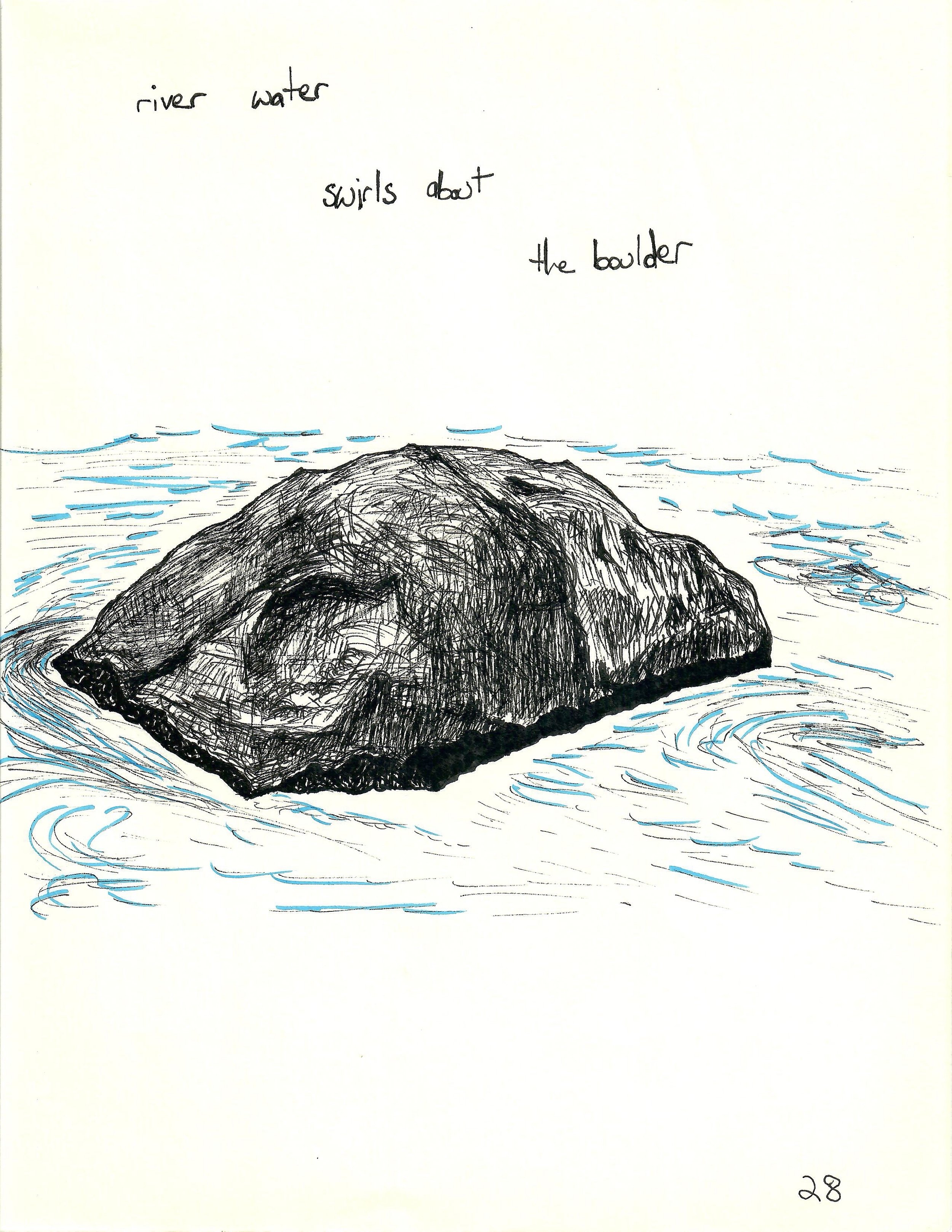

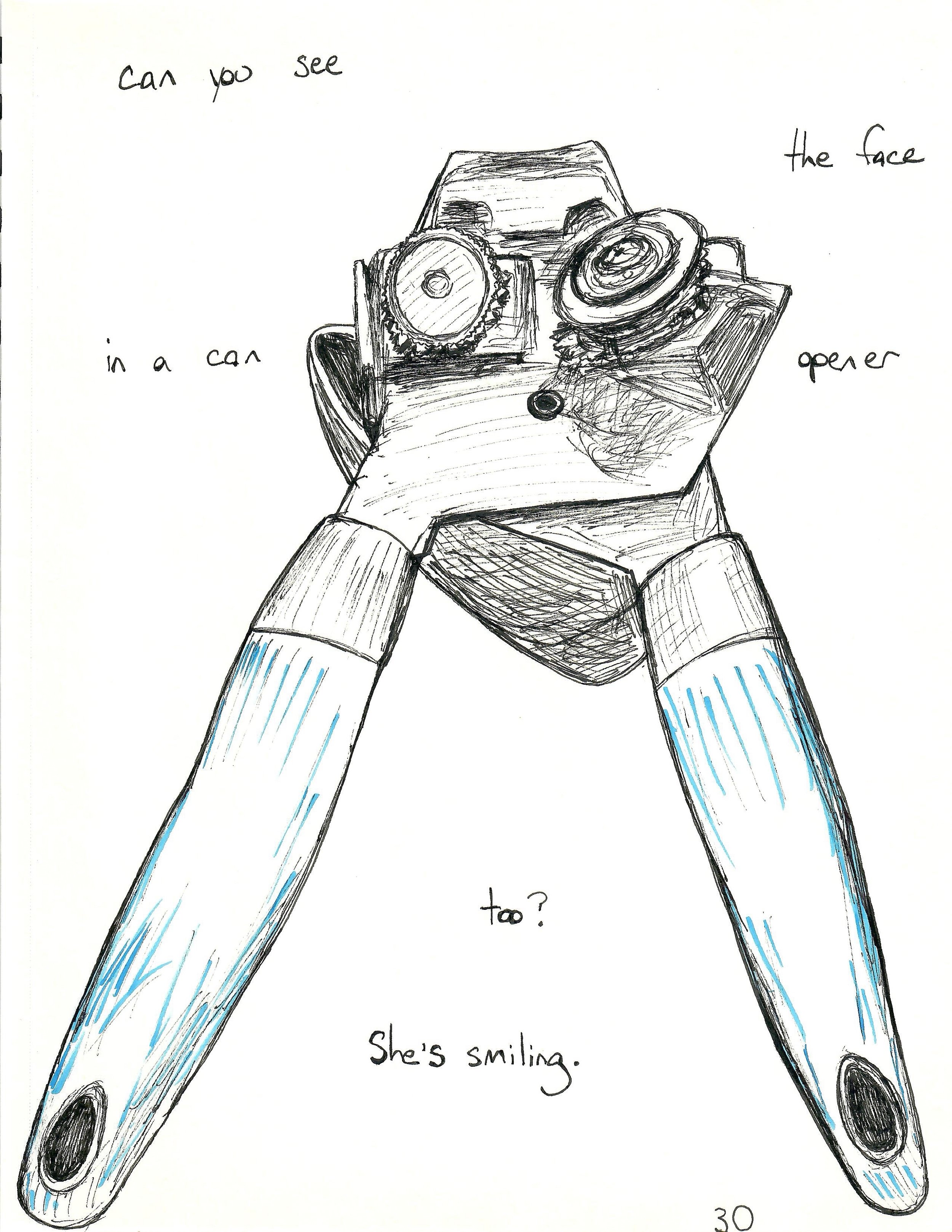

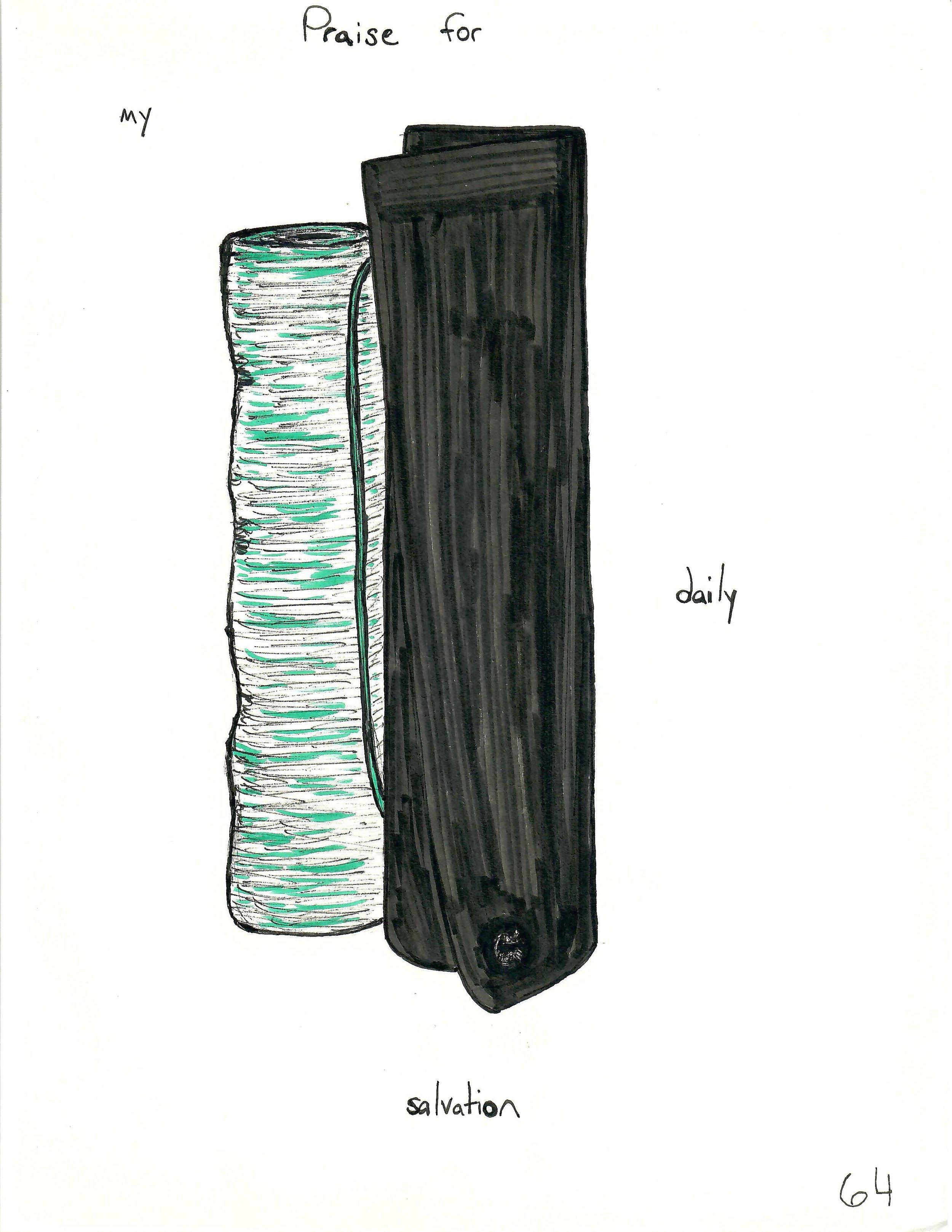

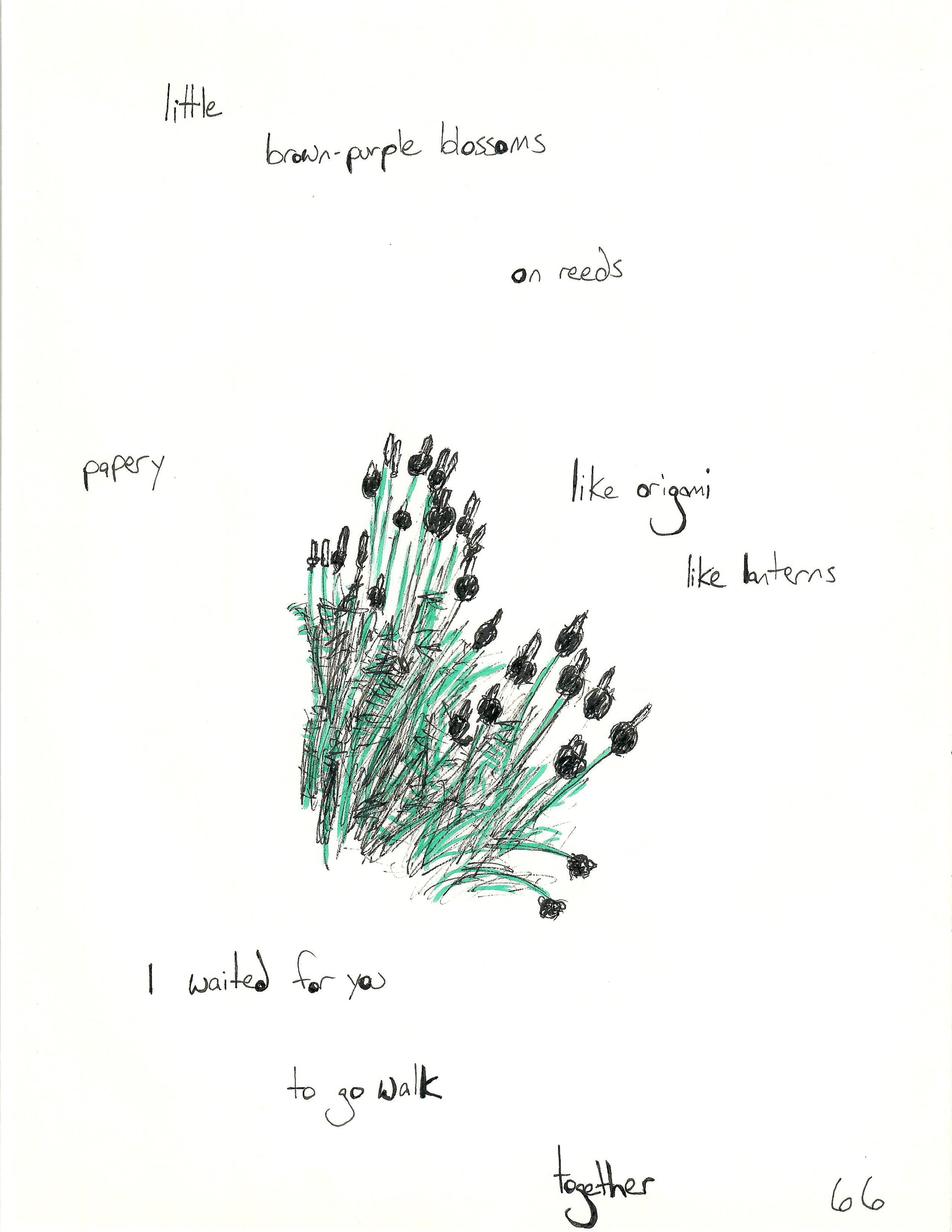

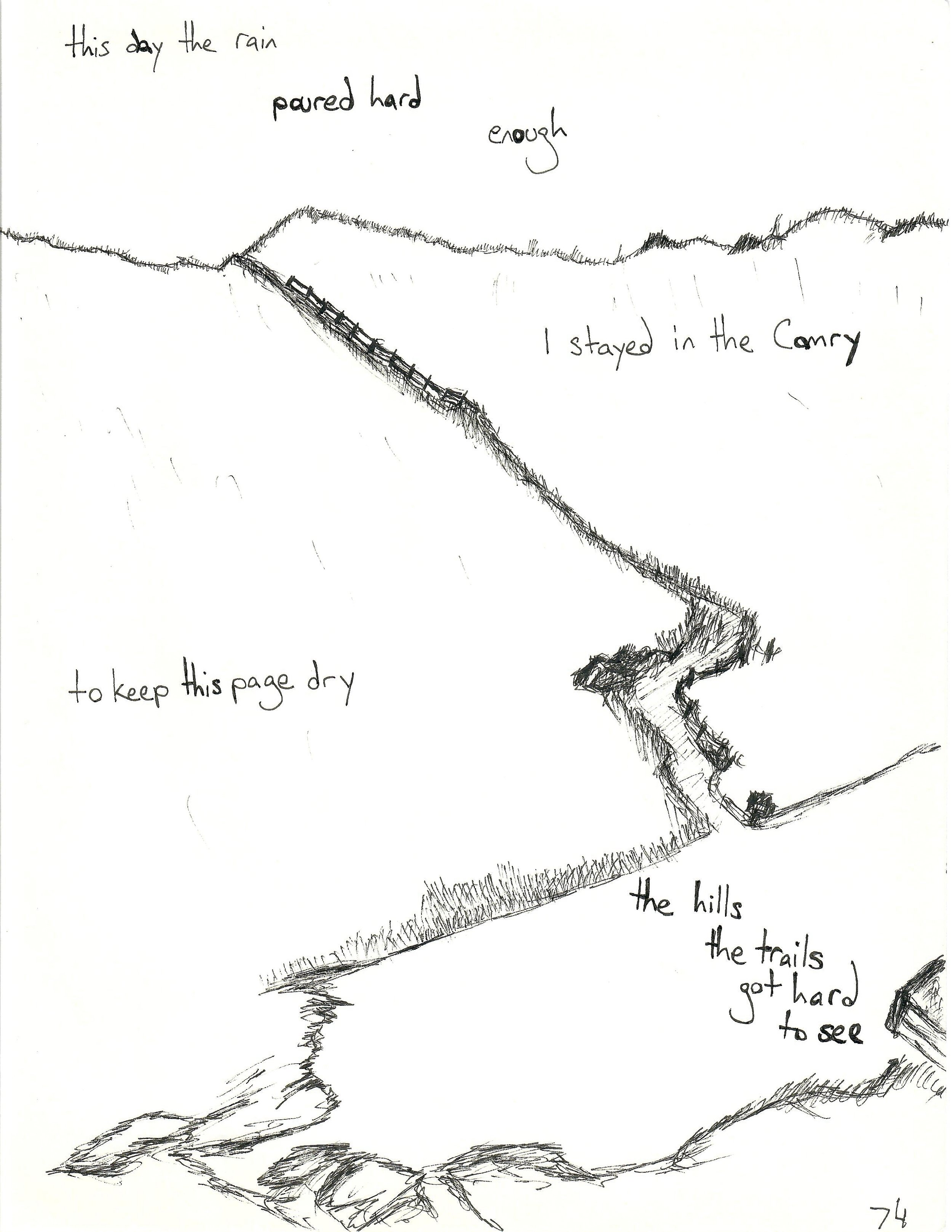

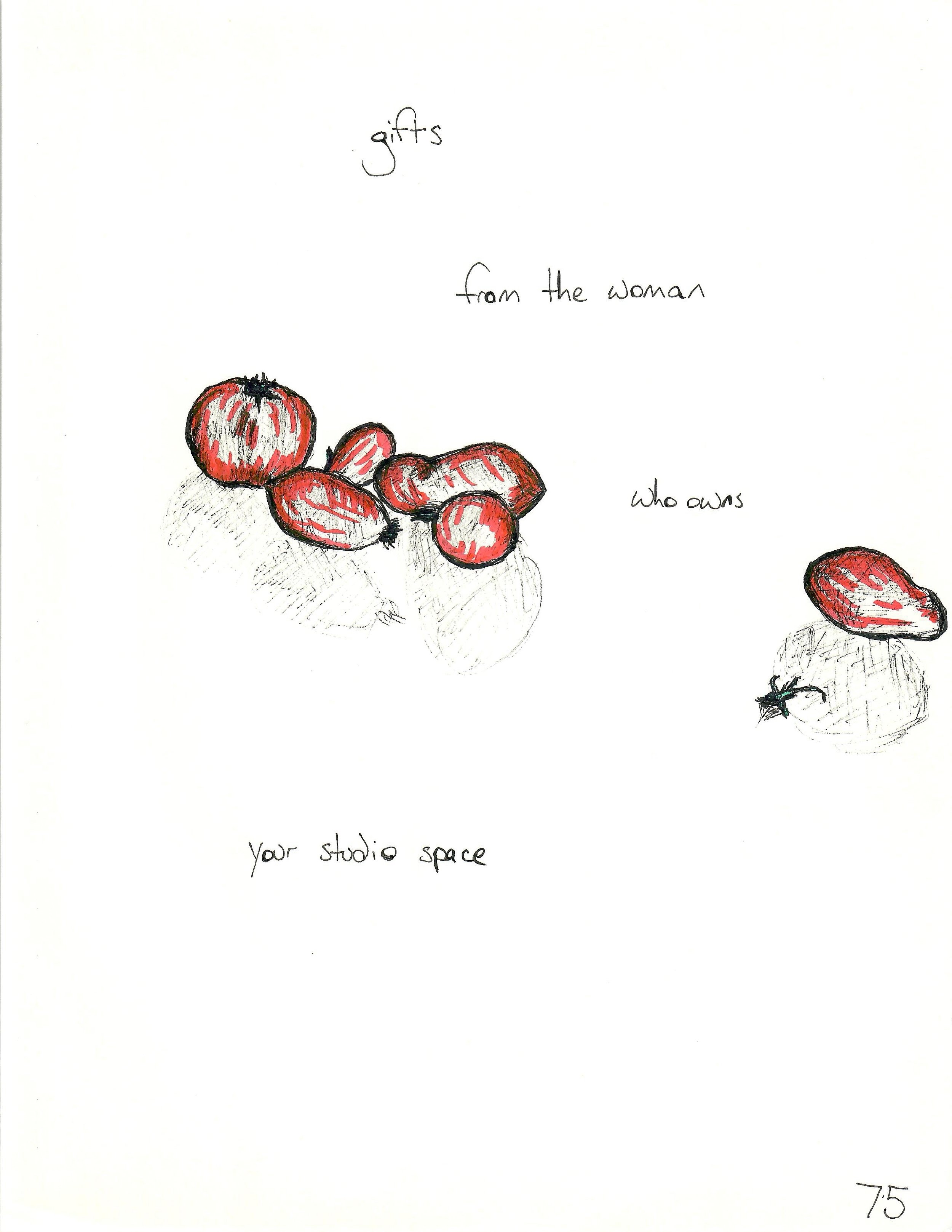

For this shared experience, I decided to make 100 drawings of objects, items, living beings, environments, all in the same sketchbook—so no do-overs—and using pigma archival ink pens—so no erasing. In my teen-and-preteen years I greatly enjoyed drawing. I've played with it here and there since then, but this isn't a discipline I've much cultivated in the last 20 years— especially drawing images in front of me rather than from memory or imagination. I wanted to let myself try something new (or old but undeveloped) and not be good at it, like an arm- balancing posture in a yoga class. I wanted to lower judgement to an appropriate level, as David Glass asks artists and creative humans to do in his workshops. I set the bar low enough for myself that I could trip over it and fall onto my sketchbook, as I learned from playwright Dano Madden, who learned that from Jeni Mahoney (who may have been quoting Rick Dresser) in reference to the writing/playwriting process.

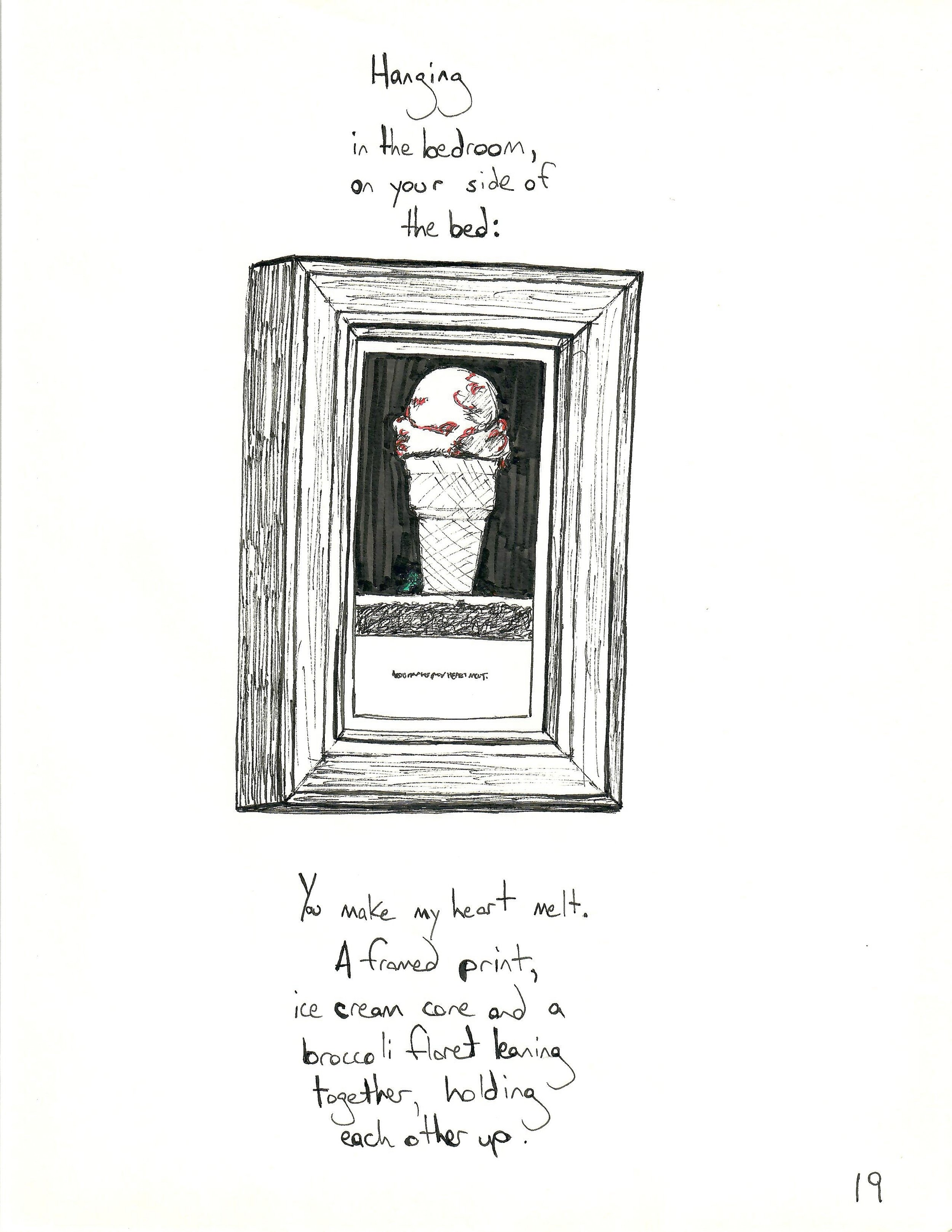

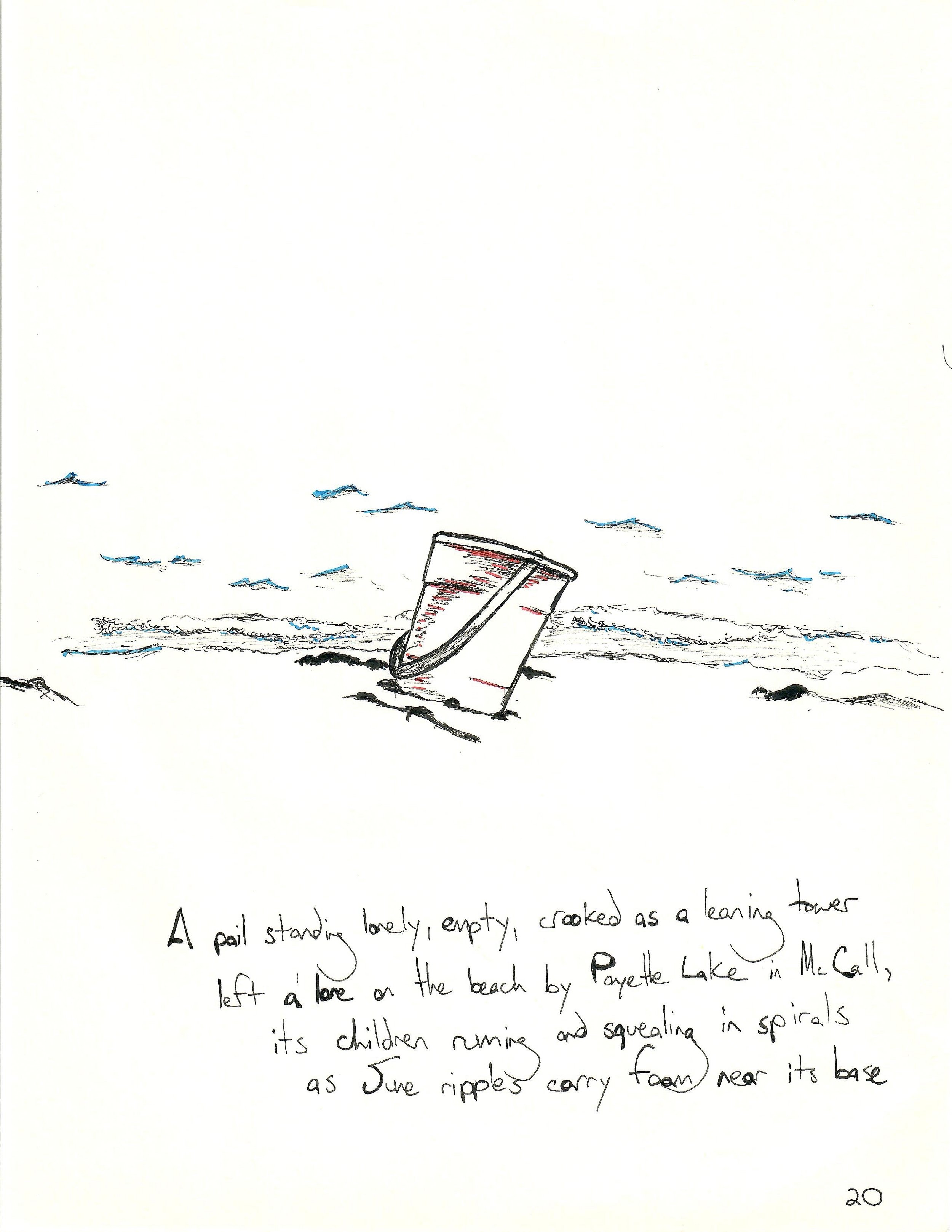

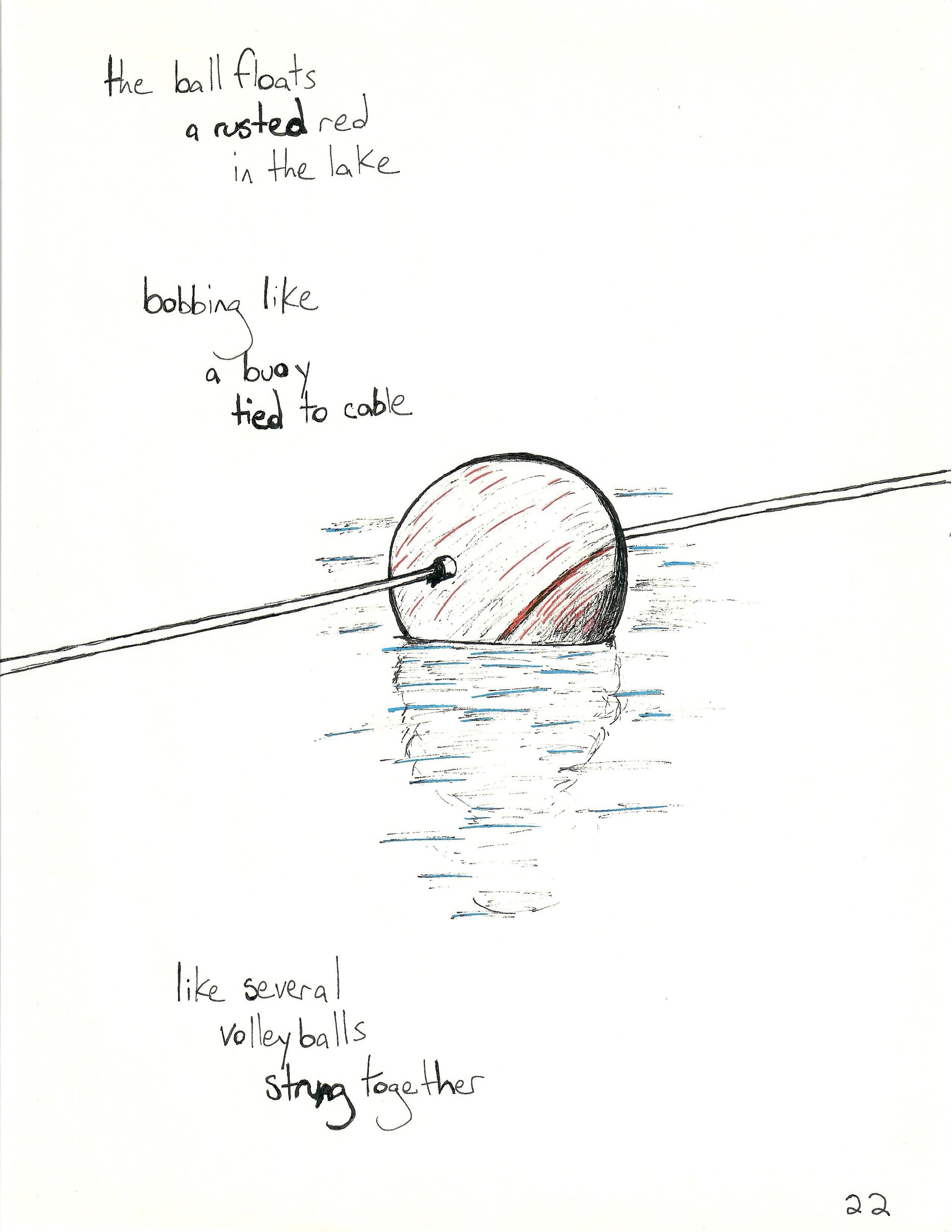

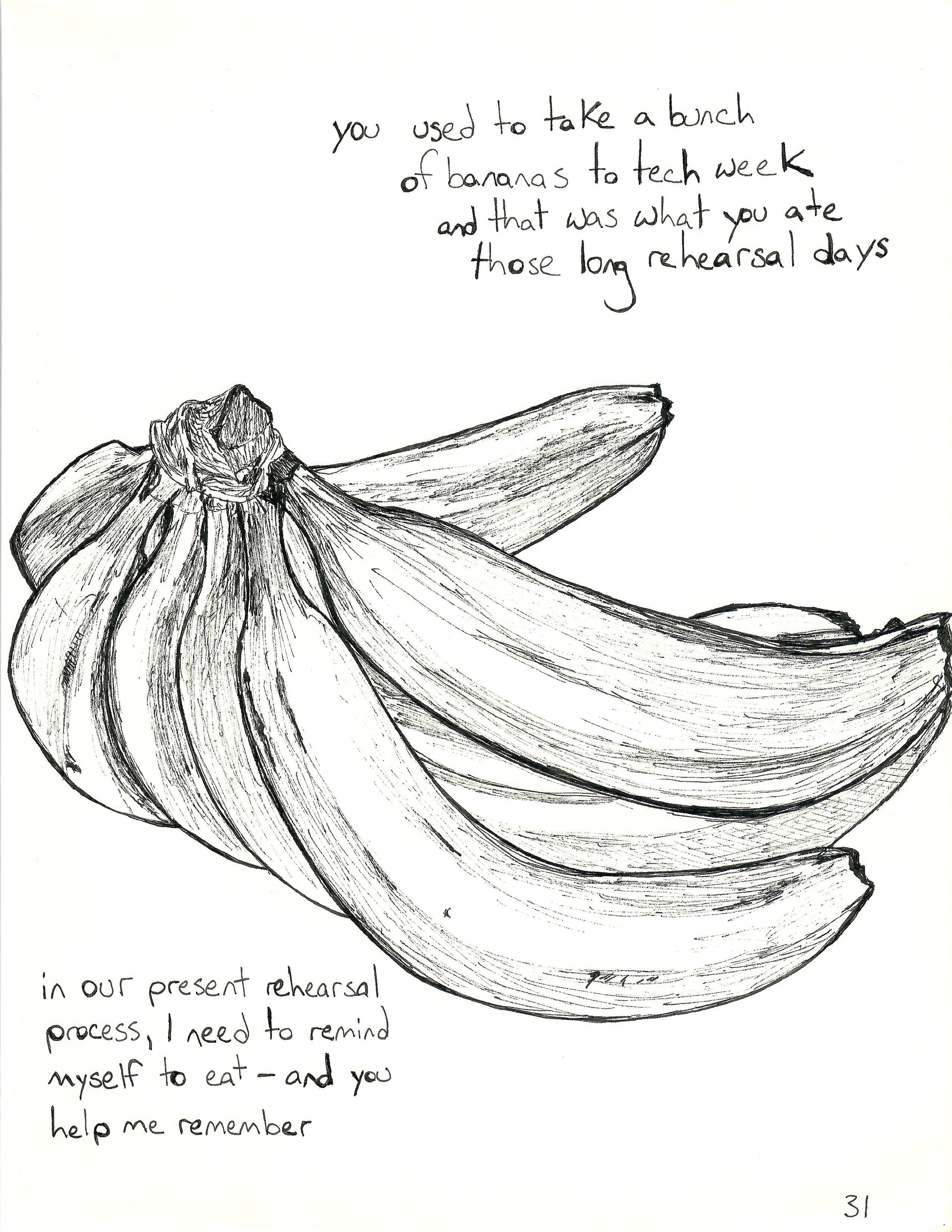

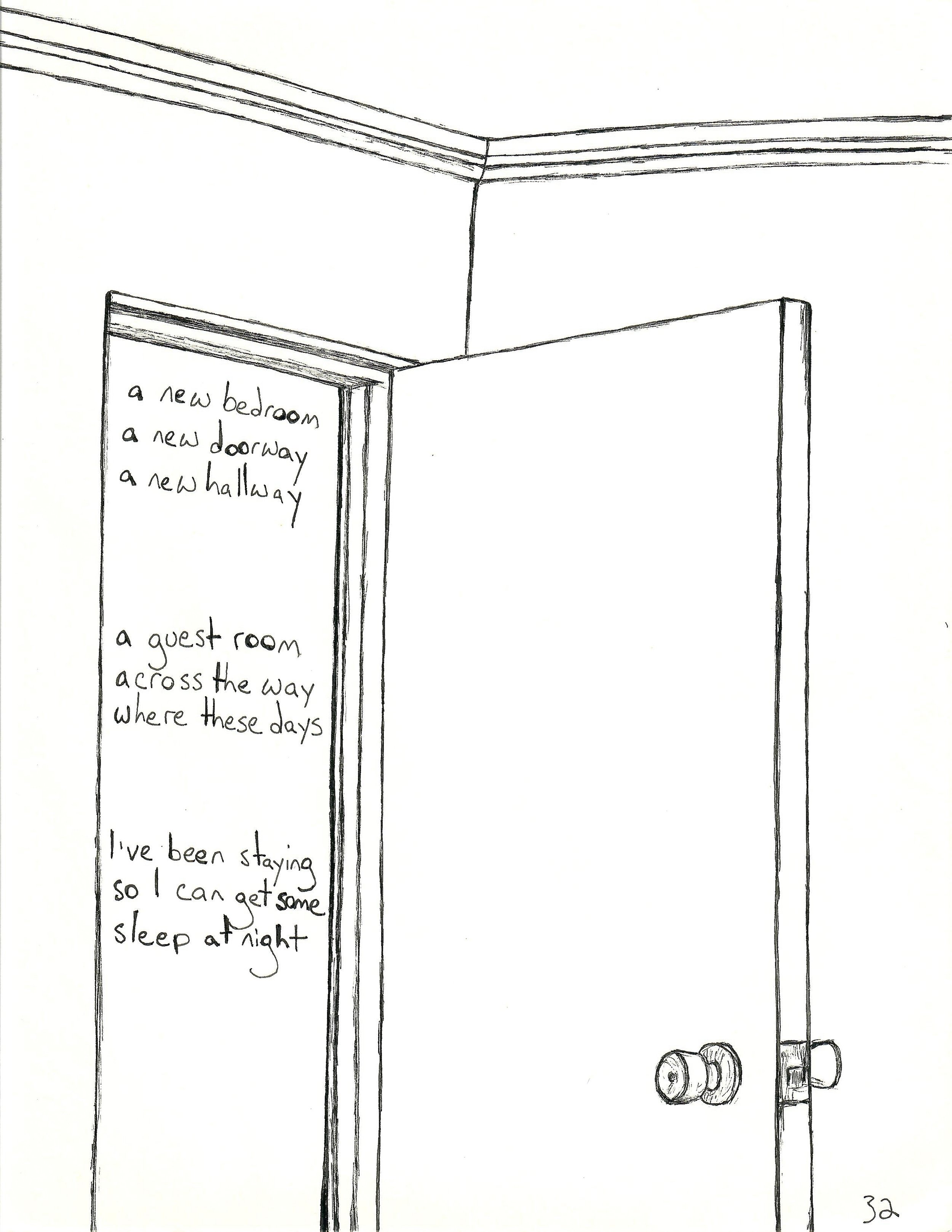

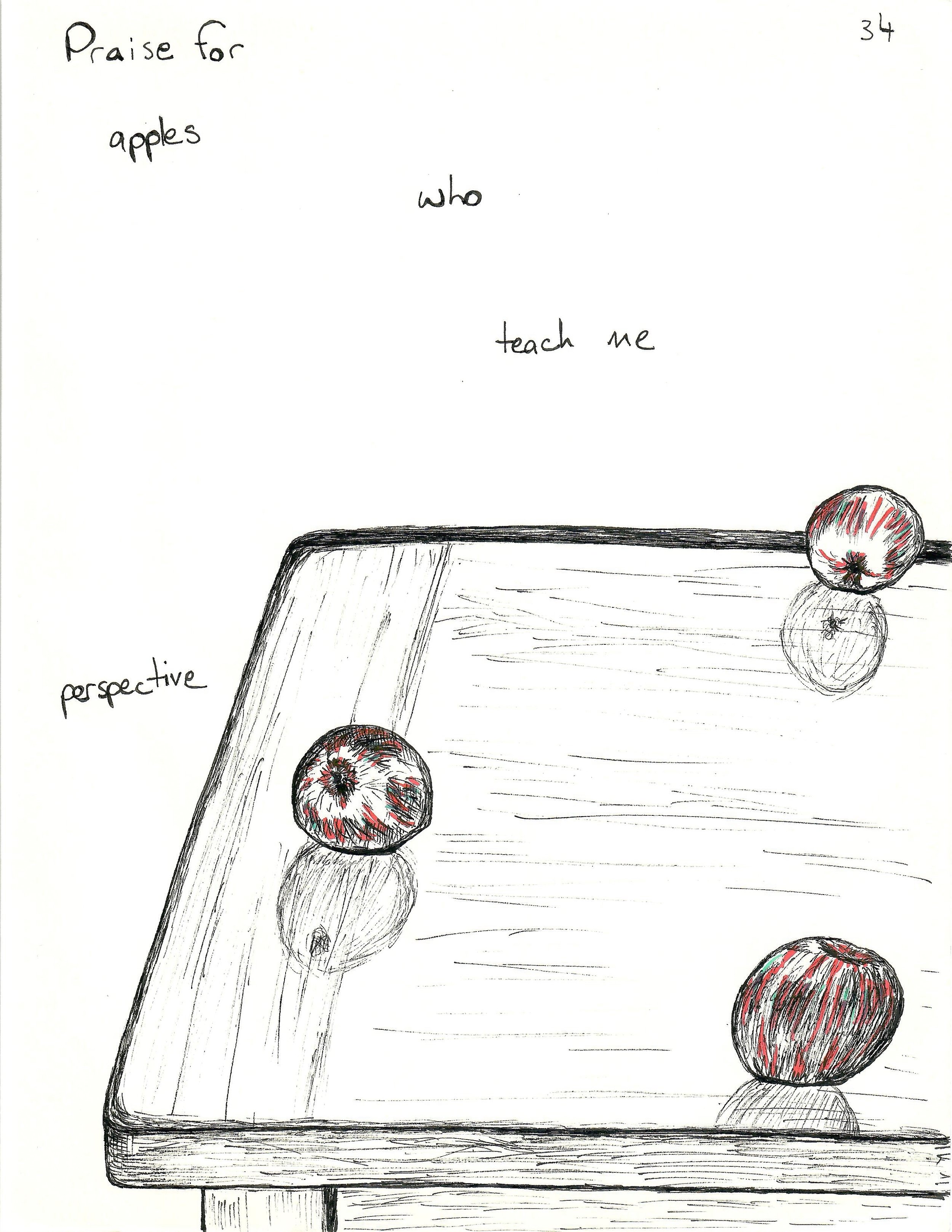

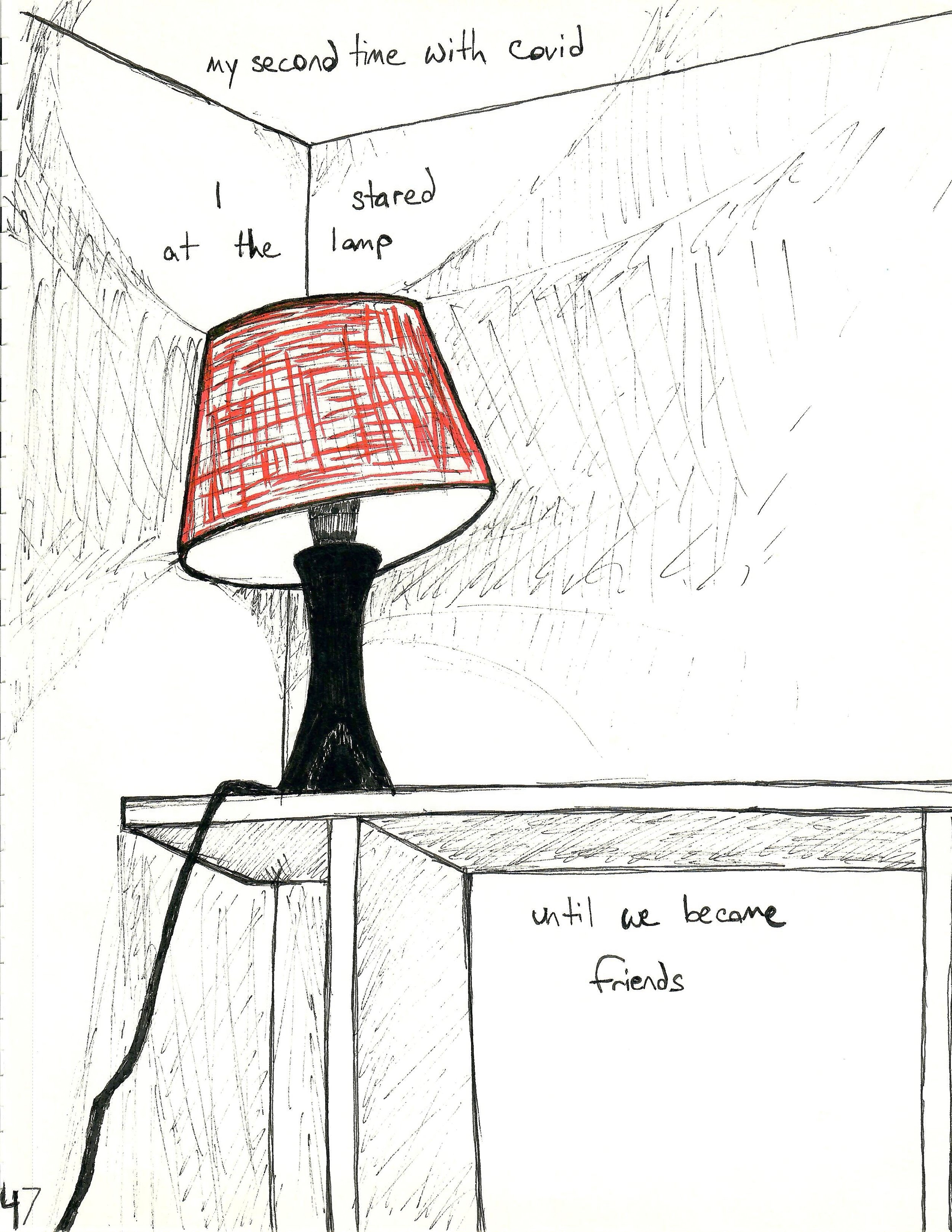

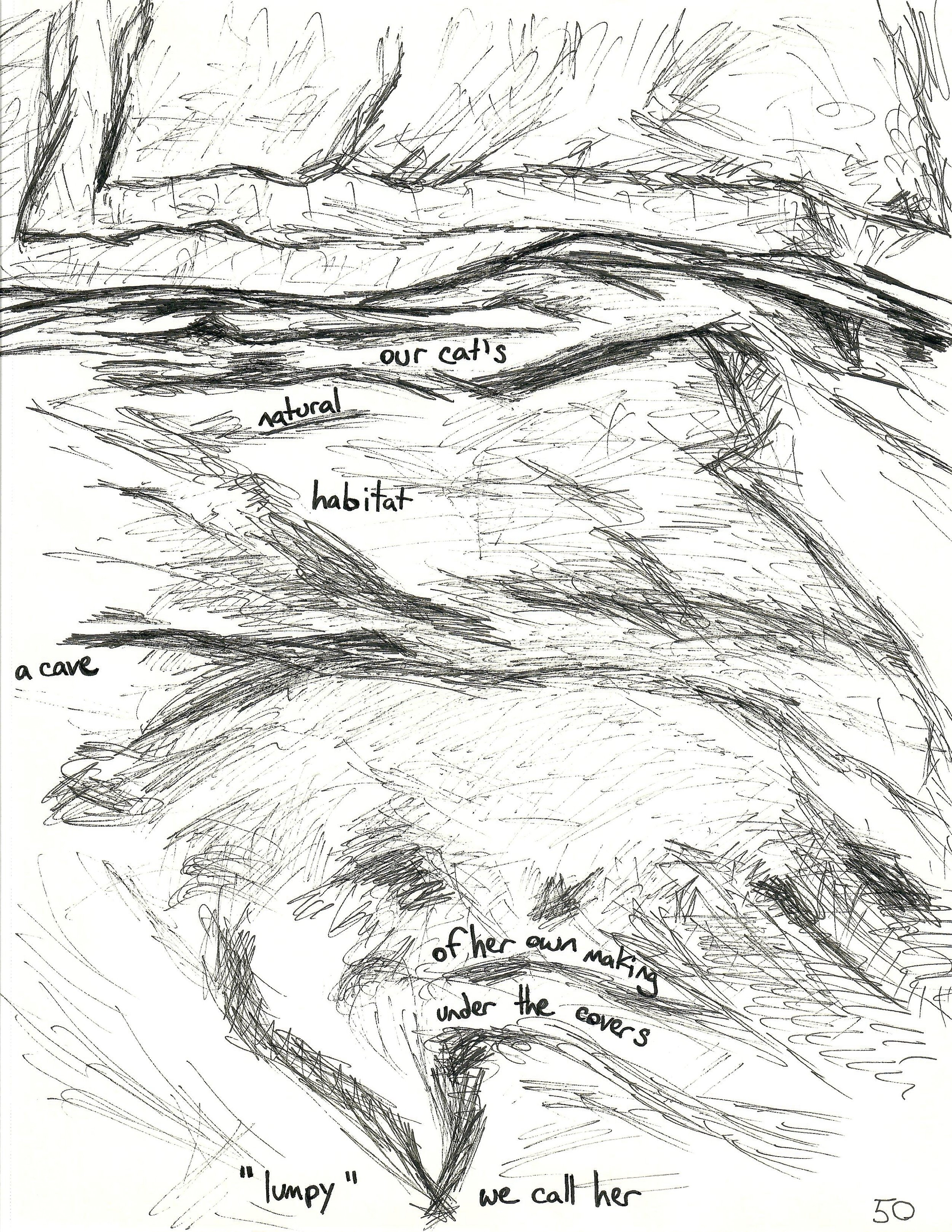

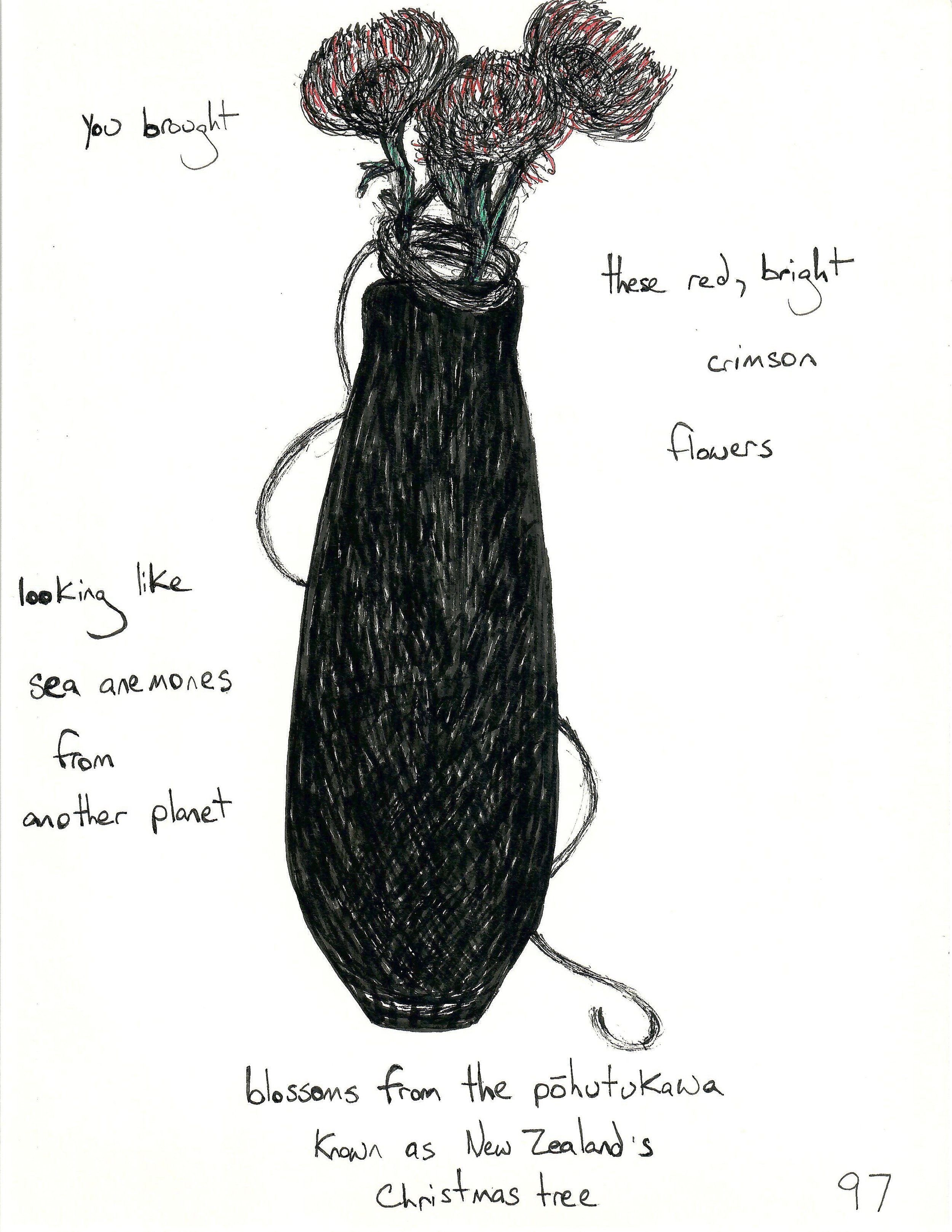

After making 100 drawings, the plan was to go back and add text, and then in a final step, go back and add to either the drawing or the text in each piece—again, without erasing. That could mean adding color, tending to shading, form, line, detail. In pairing text and image, I wanted to tend to the overarching theme by praising of everyday things, primarily by paying attention to their qualities, dimensions, articulation. This process came from an exercise I learned from writer Cindy Shearer in another durational text/image project I participated in while an MFA student at California Institute of Integral Studies.

In pursuing this project, part of me rebelled. "What are you doing? Isn't this getting in the way of your writing time? You wanted to write a new play this summer (and fall, when writing one in the summer didn’t happen). Think about all the hours that are now going into this practice and not that script."

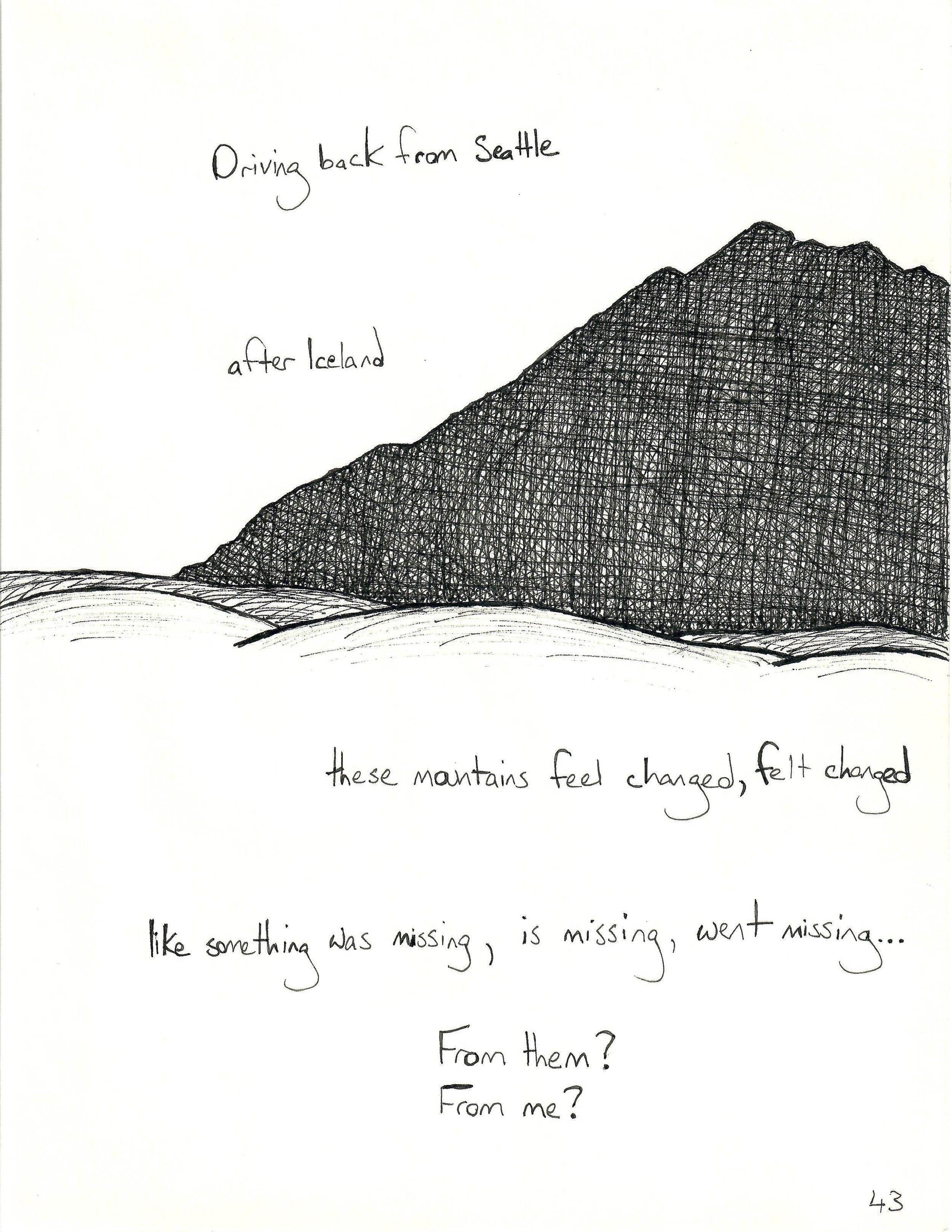

At the same time, I felt myself unlocking something deeper in my creative landscape by paying more attention to these subjects. I found that I don't really see something until I start to draw it, even more so than when I write about it. After I spend time looking and sketching, everything in the world looks more like art pieces in and of themselves. The way a light post stands tall apart from other objects in a parking lot. The shadows between every leaf in the maple out back. The way lines curve. That makes me approach the world and that day with more gentleness, more openness, more willingness to see the magic surrounding us at all times. Less judgment. It's all just stuff. We're all just stuff. It's all okay.

By paying better attention to what I'm paying attention to, through this process I started to uncover what unfolds from within. Not moving toward any finished product, I was able to discover what I uncovered: a way of seeing that I want to keep developing.

Once I got halfway through the drawing process, I started thinking more about seeing and attention. Not just what I'm seeing and paying attention to (in that moment and throughout the day/week/season/year), but the idea that whatever anyone is making, whether creatively (a play, a film, a painting, a novel), relationally (a conversation, a touch, a connection), things big and small we make in all parts of our lives (avocado toast, a plan for the day, a baby) and even what is destructive (a hate crime, a bomb, an insult) is an assemblage of what we pay attention to, what we see and what in turn pays attention to us.

Thinking about that, the simultaneous ultra-simplicity and overwhelming complexity of that, I start to pay more attention to what I'm paying attention to, how that impacts me, how that object or way of seeing makes me feel or what it makes me think about. Which makes me think about the space between those focused blips of attention: when I'm distracted, unfocused, floating away into daydreams, answering emails or sleeping. Even in those moments I'm paying attention to something (which makes me want to pay attention to whatever that is).

I wonder if this mindset is getting me paying attention with better intention, to what that means in action and what that feels like. I hope that's what's happening.

Because I'm paying attention to that intention (of how to pay attention with greater intention), then perhaps that intention is also paying attention right back to me. Magnets pulling each other closer together.

Once I got toward the end of the drawing period in my last 25 drawings, I felt the pull to be done. I had to push myself to stay present instead of rushing through to the end, especially when other creative projects were fighting for my attention. I felt how much of a durational project this was and I started getting more tired, bored and impatient. I had to find more ways to treat myself for drawing time. While I knew it wasn't, this started feeling more like a waste of time ("What? Go draw? I have a book to finish and promote! I have a play to finish! I have another play going into auditions and starting rehearsals! My students need me!").

That sense of resistance alerted me all the more that I needed to continue. In the middle-to-end stage of any process worth doing, I can feel lost at sea. This reminds me that the last 10% of a creative act can take 90% of the time, or how I can get caught up in discursive thoughts in the midst of meditation, or perhaps how an ultra-marathoner might feel in the middle-end of a long race.

Having reached 100, then having gone back to add text and then having gone a third time to add in more detail, I feel quite joyful at this stage of the work, whatever it may be. If nothing else, here is a moment of praise (not to me, but to the universe) for being able to reach 100 somethings.